Welcome to MAC Makes Music

Welcome to MAC Makes Music

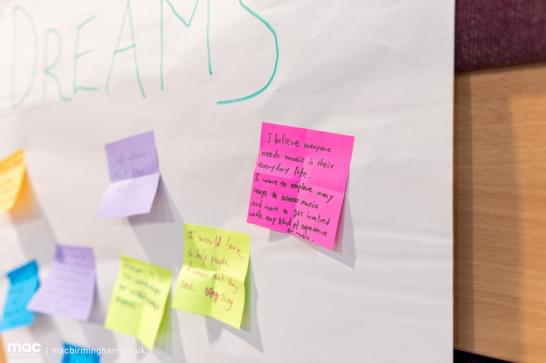

We give young people who face barriers the opportunity to make their music on their terms.

With a focus on alternative provision, our award-winning programme gives 11-25 year olds the chance to meet, create music together and express themselves through music technology, song-writing, performing and more.

Join In

Schools and More

Training and Resources

MAC would like to thank Youth Music for their continued support of MAC Makes Music. With thanks to National Lottery Million Hours Fund for PRU Projects, Arts Council England and players of People's Postcode Lottery.

Get in Touch

Contact list of staff members

Becca Williams

Orla Deacon